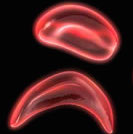

Sickle cell disease affects about 100,000 people in the United States. The disease, inherited from both parents, causes some of the patient’s red blood cells, normally shaped like a saucer, to take on a crescent or sickle shape. These malformed cells are less effective at their primary job, conveying oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body. The cells also clump together, blocking circulation and leading to organ damage, strokes and episodes of intense pain, called vaso-occlusive crises.

Sickle cell disease affects about 100,000 people in the United States. The disease, inherited from both parents, causes some of the patient’s red blood cells, normally shaped like a saucer, to take on a crescent or sickle shape. These malformed cells are less effective at their primary job, conveying oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body. The cells also clump together, blocking circulation and leading to organ damage, strokes and episodes of intense pain, called vaso-occlusive crises.

New research led by scientists at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has developed a microfluidic device that measures the stiffness of blood cells in sickle cell patients. This stiffness makes it more likely the sickle cells will become trapped in blood vessels. These measurements can be used to notify doctors when vaso-occlusive crises are likely to occur. When notified, the medical professionals can order blood transfusions that can be helpful in preventing vaso-occlusive crises.

The research is of particular importance to African Americans. While people of any race can have the sickle-cell trait, the disease is far more common among African Americans than it is among Whites. About one in every 400 African Americans is born with the sickle-cell trait.