by John K. Bollard and Catrin Lloyd-Bollard

Harvard University recently announced its decision to devote $100 million to redress the university’s ties to slavery and its legacy. This initiative brings to the fore once again the question, Who was the first African American student at Harvard? This question is not as easy to answer as one might think – and, with the recent discovery of a name buried in an 1841 Harvard catalogue, a new possible answer has come to light.

Until now, most frequently cited as the first Black students at Harvard are David Laing, Jr., Isaac H. Snowden, and Martin R. Delany, who were admitted to the Harvard Medical School in November 1850. At the time, when word leaked out that the medical faculty had voted to accept the three into the program, many of the White medical students protested strongly and threatened to leave the school. On December 13, the faculty met to discuss the matter further and decided that because Laing, Snowden, and Delany had already paid for the required lecture tickets, “the Faculty do not feel themselves authorized to revoke their arrangements,” and they reaffirmed their previous vote. As the controversy continued, they met again on December 26 to refine their decision, concluding that, while the three men would be allowed to attend the course of lectures for which they held tickets, “this Faculty deem it inexpedient, after the present course, to admit colored students to attendance on the medical lectures.” Thus they were effectively dropped from the university rolls and not allowed to continue their studies beyond their first semester. (Laing and Snowden completed their medical training through other channels and emigrated to practice medicine in Liberia. Martin Delany continued his earlier medical practice in Pittsburgh without the added benefit of a degree and as a school principal. In his later varied career, he became well known as an antislavery activist, lecturer, and author. In February 1865, he was commissioned as the first Black major in the U.S. Army in the 104th US Colored Troops.

During this controversy in 1850, 26 of the medical students did write to the faculty in support of admitting Laing, Snowden, and Delany. One statement in their petition has curiously not drawn much attention, despite indicating that the history of Black students at Harvard goes further back. The students wrote, “They remember, too, that, once before in the history of the college, this question has been decided; that a black was here received and educated more than twelve years since.” Assuming their memories serve, this would place a Black student at Harvard as early as 1838. And if one such student was suppressed, forgotten, or whitewashed from the annals of Harvard history, how many others may have been, as well?

Less notice has been given to the admission of Beverly Garnett Williams to Harvard College in 1847. Williams was born into slavery around 1830 and was probably the biracial son of an unidentified White man who sought to give his son a privileged life. He was raised by the Rev. Joseph Parker, minister of the First Baptist Church in Cambridge and educated at Hopkins Academy, a private school that prepared young men for Harvard. He excelled, especially in Latin and Greek, to such a degree that Harvard President Edward Everett commented, “The admission to Harvard College depends upon examination, and if this boy passes the examinations, he will be admitted. and if the white students choose to withdraw, all the income of this college will be devoted to his education.” Unfortunately, just before classes began in 1847, Williams died of tuberculosis. Richard Newman, late research and fellows officer at the W. E. B. Du Bois Institute, raises another possibility, “[Tuberculosis] is certainly likely, but it has been suggested, however, that Williams was murdered by irate pro-slavery advocates” Could Williams have been the “black” referenced by the medical students in 1850? It seems mostly likely not, since he was admitted just three years, not 12, before 1850, nor was he actually educated at Harvard.

Now an even earlier candidate for the title of Harvard’s first Black student has been discovered. While researching material on the history of Jim Crow in transportation, we were sifting through primary source material about Thomas Jinnings, Jr., an abolitionist who lived in Boston in the late 1830s and early 1840s. Jinnings’ father was Thomas L. Jennings, Sr., a prominent New York City businessman, tailor, abolitionist, and incidentally the first African American to be awarded a U.S. patent for his dry cleaning process. (Various family members appear as both Jinnings and Jennings, though Thomas, Jr., regularly used the former spelling.) In the Boston city directories for 1839 and 1840, Thomas Jinnings, Jr., and his brother William are recorded as living at 100 Court St., and both listed as working in the clothing business. William died in September 1840.

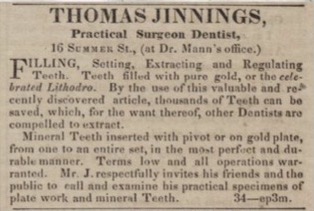

Thomas Jinnings, Jr., appears in The Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison’s weekly antislavery newspaper, on July 31, 1840, in an announcement that he would be delivering an address to the Old County (Plymouth County) Anti-Slavery Society on August 1. The address is then reported in the August 21 edition of The Liberator, but it would seem that Jinnings had left the clothing business. On the very same page we find the following advertisement (with similar ads appearing in the paper through June 10, 1842):

It was with some surprise, then, that we also found Jinnings’s name in the list of 86 medical school students and their instructors in the Harvard catalogue for 1841-42, and his instructor is listed as the same Dr. Mann as in the advertisement.

If by “here” the medical students quoted above from their 1850 petition specifically meant the Medical School, Thomas Jinnings might very well be the individual they reference (although still not quite 12 years earlier, but perhaps close enough). It is worth noting that though Jinnings is on this list and should thus be regarded as a Harvard student, his name does not appear among the 117 listed in the Harvard University Catalogue of Students Attending Medical Lectures in Boston, 1841-42. Attendance at the lectures was required for the MD degree, so it may be presumed that, as a dental student, Jinnings studied privately with Dr. Daniel Mann and did not attend the lectures, which were largely irrelevant to dentistry. (The Harvard Dental School was not founded until 1867.) Perhaps more to the point, Jinnings’s presence at the lectures would likely have been met with considerable opposition from the White students, as happened nine years later.

The summer of 1841 was a busy one for the 27-year-old Thomas Jinnings. Daniel Mann, like Jinnings, was also a staunch abolitionist, and together they attended antislavery meetings and both were elected executive board members of the new Boston Vigilance Committee, created to protect the constitutional and legal rights of persons of color. Racial tensions were increasing on the recently built New England railroads when on May 28 Jinnings bought a first-class ticket from Salem to Boston on the Eastern Railroad. After he took his seat, the conductor and a gang of brakemen, baggage masters, and a passenger physically forced him into the segregated Jim Crow car (also known as the “dirt car”).

Jinnings described the incident in a letter to The Liberator published on June 11. A number of articles and letters complaining about the frequent mistreatment of Black passengers on trains and other conveyances soon followed in other area papers. This public attention led to further attacks and protests throughout the summer and fall in which people of color, often abolitionists on their way to and from antislavery meetings, refused to leave their duly purchased first-class seats, only to be dragged, beaten, and shoved into the Jim Crow or thrown off the train altogether. Among these were David Ruggles and Frederick Douglass, twice each, and Mary Newhall Green and her infant child. Daniel Mann himself sued a railroad conductor for assault as Mann, who was White, was defending an unidentified Black passenger on the Eastern line in September. Thomas Jinnings was beaten again on the New Bedford and Taunton line in October.

Jinnings’s sister, Elizabeth Jennings, is still remembered for winning a New York Supreme Court case against the Third Avenue Railroad Company after she, too, was thrown off a New York City streetcar in 1854. This tradition of protest, begun in the 1830s by David Ruggles and given fresh impetus by Thomas Jinnings and other Boston abolitionists in 1841, took root and continued in an unbroken line throughout the country for over 130 years, through the cases of Homer Plessy in 1896 and Rosa Parks in 1955 to the Freedom Rides of the 1960s led by John Lewis and others, to name only three of many.

Whether or not Thomas Jinnings, Jr., was literally the first Black Harvard student is less important than the fact that the appearance of his name in the 1841 catalogue suggests the possibility that other unidentified African Americans may have preceded or followed him. Jinnings was only spotted in the 1841 catalogue, after all, because we were looking into his career as an abolitionist and civil rights activist. A simple name in a list tells very little about a person and certainly nothing about their racial background.

Who knows what hidden stories will come to light as Harvard’s relationship to slavery is probed more deeply in the years to come?

John Bollard is the former managing executive editor of the African American National Biography project at the W. E. B. Du Bois Institute at Harvard University. He is currently writing a book on the history of Jim Crow in travel from 1833 to 1964. Catrin Lloyd-Bollard is deputy director of programs at HB Studio in New York City.

As a Harvard alum, I read this article with great interest, and I am thankful for the diligence of the researchers in trying to set the record straight by introducing us to these now-historic figures and their stories.