Marybeth Gasman, the Samuel D. Proctor Endowed Chair & Distinguished Professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey, reviews a new book on Black women educators in Mississippi during the Civil Rights era.

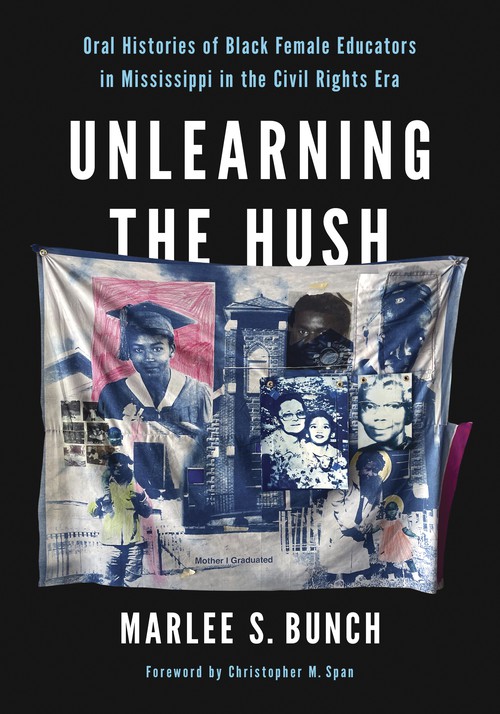

Unlearning the Hush: Oral Histories of Black Female Educators in Mississippi in the Civil Rights Era (University of Illinois Press, 2025) is a powerful and deeply human contribution to our understanding of American education and the Civil Rights era. Author Marlee S. Bunch combines oral histories, art, and poetry to illuminate the experiences of Black women who taught in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, before and after the Brown v. Board of Education decision. Their stories complicate the narrative many of us learned by showing not only the trauma of segregation and White resistance but also the joy, intellect, discipline, and love that existed within Black schools.

Unlearning the Hush: Oral Histories of Black Female Educators in Mississippi in the Civil Rights Era (University of Illinois Press, 2025) is a powerful and deeply human contribution to our understanding of American education and the Civil Rights era. Author Marlee S. Bunch combines oral histories, art, and poetry to illuminate the experiences of Black women who taught in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, before and after the Brown v. Board of Education decision. Their stories complicate the narrative many of us learned by showing not only the trauma of segregation and White resistance but also the joy, intellect, discipline, and love that existed within Black schools.

As Bunch researched Unlearning the Hush, the national landscape felt uncertain and historic. She explained, “The world was reeling, the pandemic, the murder of George Floyd, etc. As an educator myself, I found myself needing guidance and support, considering how to navigate all of the implications that societal concerns were having on classrooms.” One conversation with her mother about her mentor and former sixth-grade teacher, Mrs. Jemye Heath, shifted everything. As Bunch shared, “It was all it took to spark what would become my research area, and the beginning journey for Unlearning the Hush.”

Her family’s history made the work deeply personal. Bunch shared, “My grandmother taught for nearly 40 years in Hattiesburg, Mississippi.” She added, “My mother attended segregated schools in Hattiesburg, and so I was familiar with the stories she shared.” The research enabled Bunch to explore both personal memory and the broader history of education in the Jim Crow South in greater depth. She stated, “The research for the book allowed me to not only explore family history more intimately, but also the history of education on a broader level.”

Bunch wanted to build a book that felt alive. She combined oral history, visual art, poetry, and archival materials, an approach she describes as “the quilting together of the artistic, academic, histories, and stories.” Many of the women she interviewed spoke about the influence of poetry, art, and Black history in their lives and teaching. “For example, Dr. Joyce Ladner spoke about my grandmother introducing her to Margaret Walker’s poem, For My People.” Those seemingly small classroom moments served as the impetus for student identity, ambition, and achievement.

Bunch hopes this structure gives readers multiple pathways into the material. As she shared with me, “My goal was to create a book that could be read in multiple ways, allowing readers to experience it in various ways. Sometimes a traditional format can flatten the dimensions of stories and histories. This structure allowed me to create a narrative space where the reader can feel, see, as well as learn, and where the humanity of the people at the center of the work remains visible and celebrated.”

What emerged most clearly from the interviews that Bunch conducted was a portrait of educators who taught the whole child and understood the weight and the promise of their role. Their work predated terminology that is now common in teacher preparation programs. Bunch shared, “They were using what we now consider culturally responsive practices and social-emotional learning, well before we had names for them.” Whether introducing global learning and Black history, making home visits, or simply reminding children of their own brilliance, they helped cultivate pride and possibility. Former students described classrooms that were “rigorous, joyful, and affirming,” and teachers who served as mentors, guides, and role models for their lives.

From the start, Bunch wanted to avoid reducing these teachers to victims of an unjust system. “When I began this project, I knew I didn’t want to reproduce the deficit narrative about Black teachers living under Jim Crow. We have all heard that story.” The structural violence was real, according to Bunch. However, she noted, “They were faced with policies that restricted their salaries, their mobility, and even the resources available to their students.” Many could not pursue advanced degrees without relocating to another state. But those truths were not the whole story. She explained, “When they spoke, what rose to the surface wasn’t only pain; it was laughter, pride, devotion to children, and the creativity that flourished in Black classrooms and communities.” From Bunch’s perspective, the joy she heard was not naïve. It was “a deliberate act of survival and community-building, and that is an important part of the story that also needs to be told.”

What is beautiful about Unlearning the Hush is that the process of gathering these histories shifted Bunch’s own life. As she shared with me, “Bearing witness to the stories and lived experiences of the contributors was transformational for me.” For Bunch, interviewing elders, many of whom had shaped her own family, came with a sense of reverence. She stated, “I approached each interview exactly how I felt, which was that I was in the presence of a wise elder, a guide, kin.” Bunch saw her role not as a gatekeeper but as a steward, noting “The responsibility and goal weren’t to produce a perfect historical record, but to protect the integrity of their stories and agency.”

The project became a shared endeavor for Bunch and the women whom she interviewed. She explained, “In many ways, the process became a collaboration, one driven by love, reciprocity, and a profound respect for the lives they lived and the histories they carried.” Interviewees weighed in on every detail, from the inclusion of artifacts to the book’s title. Bunch stated, “Because my story is intertwined with their stories, it was an endeavor that required patience, and the intentional effort to remain committed to telling their story in the way they wanted it shared.”

Unlearning the Hush reminds us that the history of Black education in this country has always been more than resistance to injustice. It is also a history of ingenuity, rigor, and love. Bunch gives these women their time in the spotlight, not a mere footnote in a court case, but as true architects of possibility who shaped generations of young people. Their classrooms were filled with high expectations and deep care, and their commitment to Black children helped to create and fuel a movement. By listening closely and honoring their voices, Bunch ensures that we do not forget who made so much of our nation’s progress possible. Unlearning the Hush invites its readers to remember and to learn, but most of all to speak the names and wisdom of the women who refused to be quiet.