![]() Once more, this year The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education has completed its survey of admissions offices at the nation’s highest-ranked research universities. For the 23rd consecutive year, we have calculated and compared the percentages of Black/African-American students in this fall’s entering classes. As in the past, our survey publishes information on the total number of Black applicants at the various institutions, their acceptance rates, enrollment numbers, and yield rates (the percentage of students who eventually enroll in the colleges at which they were accepted).

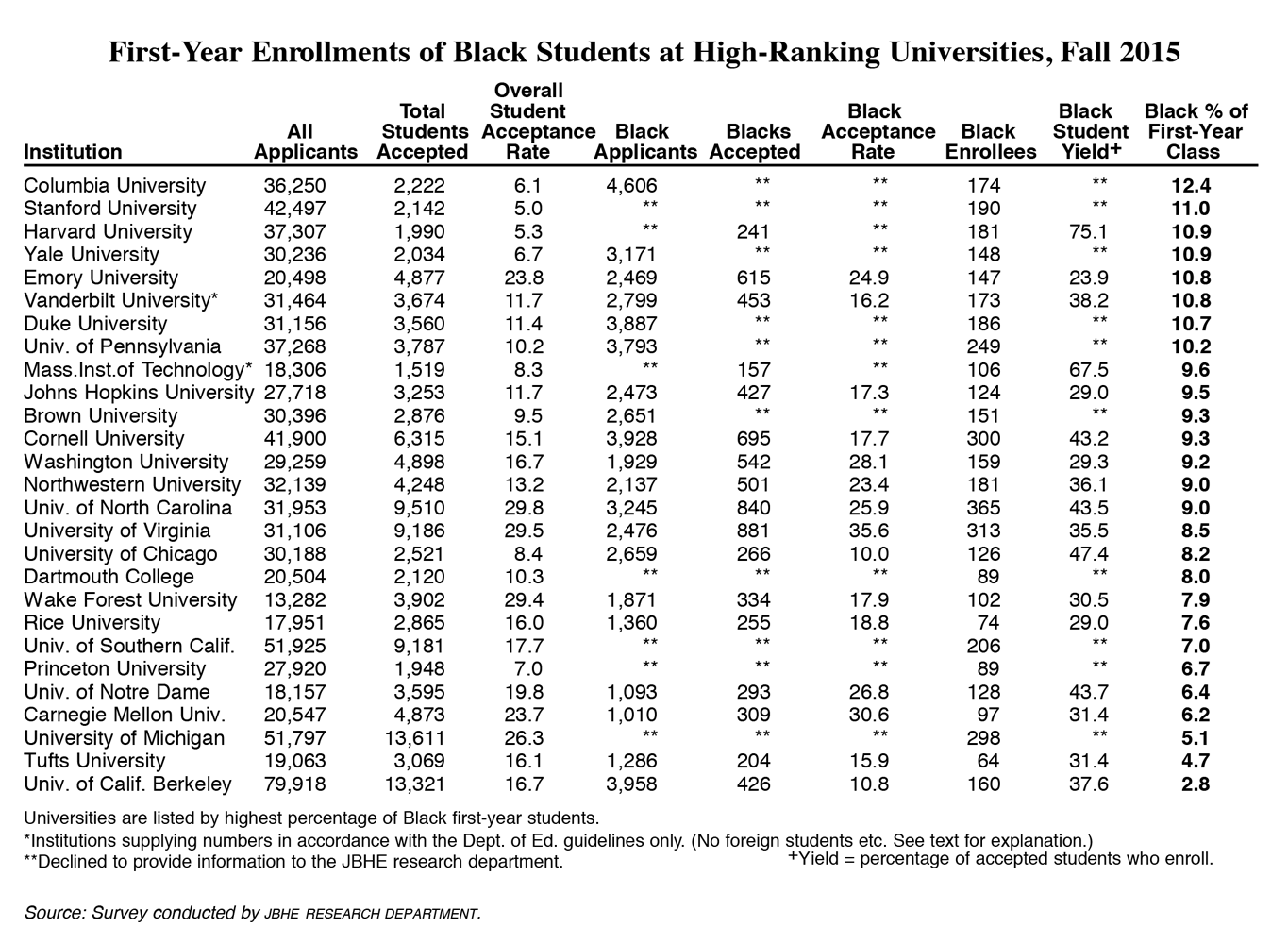

Once more, this year The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education has completed its survey of admissions offices at the nation’s highest-ranked research universities. For the 23rd consecutive year, we have calculated and compared the percentages of Black/African-American students in this fall’s entering classes. As in the past, our survey publishes information on the total number of Black applicants at the various institutions, their acceptance rates, enrollment numbers, and yield rates (the percentage of students who eventually enroll in the colleges at which they were accepted).

Eight years ago Columbia University headed the JBHE rankings for the first time. Now, for the ninth year in a row, Columbia has the highest percentage of Black first-year students among the 30 highest-ranking universities in the nation. There are 174 Black first-year students at Columbia this fall. They make up 12.4 percent of the incoming class.

Only 11 years ago in 2004, Blacks made up only 6.8 percent of the entering students at Columbia University. In 2010, there were 202 Black first-year students at Columbia. They made up 14.5 percent of the incoming students. This was the highest percentage of Black students in the entering class at a leading research university in the history of the JBHE survey. Last year, Black students were 14.1 percent of the students in the entering class at Columbia.

There is very little difference in the percentage of Black first-year students at the universities ranking second through eighth in our survey. In fact, there is only a 0.8 percentage point difference between the university ranking second and the university ranking eighth.

Stanford University has an entering class that is 11 percent Black. This places Stanford in second place in our survey. Stanford ranked sixth in last year’s survey.

Harvard University and Yale University tied for third place in our survey with first-year classes that are 10.9 percent Black. Closely behind, and in a tie for fifth place, are two southern universities, Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, and Emory University in Atlanta. Both have entering classes that are 10.8 percent Black.

Duke University and the University of Pennsylvania also had first-year classes that were more than 10 percent Black.

Slightly more than a decade ago in 2004, only two of the nation’s highest-ranked universities had incoming classes that were more than 10 percent Black. This year there are eight high-ranked universities with an entering class that is more than 10 percent Black. This is a major sign of progress for African Americans at our top universities.

The bottom place in our survey belongs to the University of California at Berkeley, which is prohibited by state law from considering race in their admissions decisions. The percentage of Black first-year students at Berkeley remains significantly below the level of Black enrollments that existed before that state enacted a ban on race-sensitive admissions.

Gainers and Losers

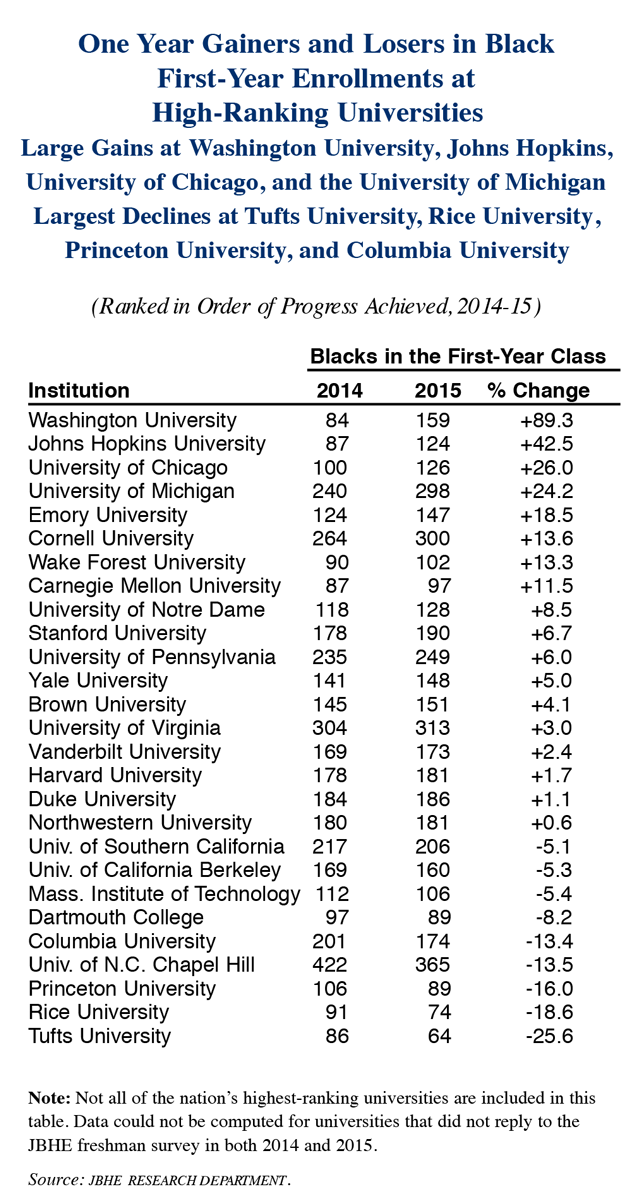

This year 18 of the high-ranking universities that responded to our survey in both 2014 and 2015 showed gains over the previous year in Black student first-year enrollments. Only nine high-ranking universities showed declines in their number of entering freshmen who are Black. A year ago, the exact same number of leading universities had increases compared to those who showed declines.

The largest gain this year by a large margin was at Washington University in St. Louis. The city of St. Louis and the state of Missouri have been the focal point for Black student protests that expanded to universities across the United States in 2015. There are 159 Black first-year students at Washington University, up from 84 a year ago. This is a whopping increase of 89.5 percent.

Admissions officials at Washington University told JBHE that “our number is still relatively small and we hope to continue to make progress as our efforts expand further.” The spokesperson listed the following reasons for the significant progress achieved this year:

- Additional funding for scholarship support and, therefore, more opportunities to provide financial aid.

- Additional targeted outreach efforts by Admissions Office staff and campus partners.

- More referrals of prospective students/families from our alumni, current students/families, and others.

- Expanded partnerships with college access programs and community based organizations.

- Larger number of prospective student visitors during a special fall visit program for high school seniors.

- Larger attendance and diversity at summer programs for high school students.

- The university’s general commitment to enhancing the diversity of the student body, staff and faculty and, in particular, the appointment of a number of key university leaders who are African-American and who are well-known in their fields.

John Hopkins University in Baltimore also posted significant gains. There are 124 Black first-year students at the university. A year ago there were 87. This is a significant increase of more than 42 percent.

The largest percentage decline in the number of Black entering students occurred at Tufts University in Massachusetts. There are 64 Black students in the entering class at Tufts. This is down from 86 Black students in last year’s entering class. Other universities with significant declines of more than 13 percent were Rice University, Princeton University, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Columbia University. Yet, despite Columbia University’s significant decline, the university continued to have the highest percentage of Black first-year students among the leading research universities.

A Note on Methodology

Before we continue with the results, it is important to mention how the U.S. Department of Education collects data on the race of undergraduates. Before a change was made several years ago, students who reported more than one race (including African American) were included in the figures for Black students. This is no longer the case. Thus, students who self-identify as biracial or multiracial with some level of African heritage are no longer classified as Black by the Department of Education.

JBHE surveys have always asked respondents to include all students who self-identify as having African American or African heritage including those who are actually from Africa. JBHE has always maintained that biracial, multiracial, and Black students from Africa add to the diversity of a college campus. And including these students in our figures offers college-bound Black students a better idea of what they can expect at a given college or university. In order that we can compare our current data to past JBHE surveys we have continued to asked colleges and universities to include all students who identify themselves as having African American or African heritage.

Some of our responding universities chose to report results that correspond with official Department of Education figures. They are indicated on the main table with an asterisk. It should be noted that if biracial, multiracial, and Black foreign students were included in the Black percentage of students in the first-year classes at these institutions, the overall percentage of Black students would undoubtedly be higher.

Black Student Acceptance Rates

It is well recognized that the percentage of Black applicants who actually receive invitations to join the entering class is a valuable gauge of an institution’s commitment to racial diversity. Yet this figure is regarded as the most sensitive of all admissions data. This is particularly true for some of the very highest-ranked institutions.

Of the 27 highest-ranked universities in our survey this year, 12 declined to reveal their Black student acceptance rates. Unquestionably, public and private litigation threats to affirmative action policies in college admissions have been a factor in producing this sensitivity. With this in mind, admissions officers — who on the whole are solidly supportive of affirmative action — have apprehensions when statistics on Black admissions are made available to the public. There are standard concerns too that racial conservatives on faculties and among alumni and trustees may interpret the figures as suggesting a so-called dumbing down of academic standards and a favoring of “unqualified” Blacks over perhaps more qualified Whites.

But, at the same time it is critical to keep in mind that an institution’s high Black acceptance rate often indicates nothing more than the fact that the admissions office of a given institution has a very strong and well-qualified Black applicant pool.

At 11 of the 15 universities that supplied acceptance rate data to JBHE, the Black student acceptance rate was higher than the acceptance rate for all students. In some cases the differences were significant but larger disparities have been seen in prior surveys. The two universities that showed the biggest gains in Black students this year – Washington University and Johns Hopkins University – both had a significantly higher acceptance rates for Black students than for students as a whole. Four of the high-ranking universities we surveyed had Black acceptance rates that were in fact lower than the overall acceptance rate.

Of the 17 universities that reported Black student yield, the highest rate was at Harvard University. At Harvard, more than three quarters of all Black students accepted for admission decided to enroll. Among the reporting universities, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology ranked second in Black student yield with a rate of 67.5 percent.

i would like to see the rates of graduates rather than acceptance. the problem isn’t about being accepted considering affirmative action , the focus should be about the black graduating rate in those institutions.

the schools are willing to accept minorities to better their quota but it doesn’t help the student when they have to deal with such a strenuous curriculum

Graduation rates are available here. You can see that the Black student graduation rate at most of these universities is very high and in many instances very close to the rate for White students.

There are obviously much more sophisticated arguments than what Shawn provided that make the same claim to greater effect.

It’s not so simple as just stating the black students have graduation rates similar to that of whites.

One thing I would seek data on… Do black students typically study for degrees that have as great rigor and demand as the degree that white students study for? Are blacks equally represented in physics, mathematics, engineering, and the various other hard sciences, and/or is there elevated representation in the “soft” fields, some which were recently tailored, such as black studies, for example?

Another thing I’d submit. I would produce data that suggests that grade inflation is rampant among elite institutions. Let’s say that among wealthy parents of mediocre students, there is a certain expectation that their student’s grades mirror those of their peers. Nothing is too good for Johnny boy, after all.

Now, if evidence is present that grade inflation is prevalent at institutions with average 2200+ SATs, why would I not believe inflation exists, and may be even more pronounced, in the black student cohort with average SAT of 1800?

More briefly, why should we not believe that black students benefit just as much from grade inflation, or more, compared to other students? No one has said teachers grade them more strictly.

Another comment which I forgot to include earlier.

Students at elite colleges are necessarioy and by extension, elite students. Is it a proper comparison to compare the stats of the future generation of black scientists and legal scholars with those of the ordinary black student, who may well come in requiring remedial coursework, and for that matter the junior college student, or the first-generation college student?

What has to be considered in conjunction with that: Do the favorable numbers hold up as one moves down the tiers of the elite colleges to schools whic are only regionally prestigious? I’m not sure they do. My guess is that the high stakes admissions in the first toner actually result in a deficit of scholarly ability at the lower levels. What I mean by this, there’s a greater pressure among these institutions, say one with <10% black student body membership, to acquire black students of top talent. Because of the aggressive recruitment, it may well be that students whose talent places them at a state school or Tier Two school are being absorbed into more prestigious institutions, which has the unplanned effect that students at the state schools may be less prepared. Then if the numbers bear that out, you'll see high levels of success and graduation at top institutions, but as one moves down the listing to average schools, then the numbers drop off and no longer seem favorable.

That's a particular interpretaton, that many people believe is present in the data. It's not only pertinent to show student success at the best institutions; but, do blacks enjoy similar results at institutions at all levels?

In the past Georgetown was included in the statistics. Is there a reason they are not on the list?

We did not receive a response to our survey.